Evil is not a surpassing (though those who glorify evil consider it so), it is a degeneration. Of course humans cannot surpass God in stuff where surpassing applies. God would be the perfection implied by ‘degeneration’. It is not God who is degenerating — He is distinct from His creation, though also intimately relating with it. Humans, in the image of God, degenerate apart from Him — the only way back is atonement.

In a sentence: evil is “good messed up”. Without good, you cannot have evil. But – you can have good that is not messed up. You don’t have to have something “messed up” right next to something “not messed up” in order to appreciate the goodness of something that is “not messed up”.

Now, in my “Predestination and Free Will” thread, it pointed out that evil is a “privation” like rust or rot. Evil, rust, and rot do not happen in and of themselves – they happen TO things that start out good. Even if you “don’t know what ya got (good) ‘til it’s rusted and rotten (evil)” – the fact remains, it was good first.

That’s why (if it happened according to Genesis) God said “don’t eat the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil” – we’re better off not knowing the difference. We’re better off innocent. We’re better off thinkin’ “It’s all good.” But it would not have been love if He had actually prevented us from making that choice.

Also from the same book I quoted in “Predestination and Free Will”, it points this out:

“(1) Good and evil are either judged by a standard beyond themselves or they are judged by each other.

(2) But if they are judged by a standard beyond themselves, then that is the one and only ultimate by which all is judged (which is actually the theistic definition of “God”).

(3) If good is judged by evil, then evil is the single ultimate by which all else is measured.

(4) If evil is judged by good, then good is the single ultimate by which all else is measured.

(5) In both cases there is one, not two, ultimate standard (contrary to dualism).

“Further, as Augustine pointed out in reply to the Manichaeans, evil is measured by good and not the reverse. For when we take all that we call evil away from something, then what is left is better (for example, remove all rust from a car and one has a better car). But when we take all that is good from something, then nothing is left. Good, therefore, is the positive and evil is the privation, or lack of good,” (330-331, Introduction to Philosophy: A Christian Perspective; Geisler, Feinberg).

Now – maybe you got messed up by number 2 up there and began to ask, “Well – if God is the judge of good, then that means God is not good.” Not so. Since when does judging whether or not something is evil or good make you “not good”? All those numbers are saying is that good and evil are not coeternal opposites. God, who is good, is the only eternal ultimate by which good and “the privation (but not opposite) of good” (evil) are judged.

Review this relevant part of that quote I was talking about:

Evil is not a “thing” (or substance). Evil is a privation, or absence of good. Evil exists in another entity (as rust exists in a car or rot exists in a tree), but does not exist in itself. Nothing can be totally evil (in a metaphysical sense). One cannot have a totally rusted car or a totally moth-eaten garment. For if it were completely destroyed, then it would not exist at all. The Christian points to Scripture which says everything God made was “good” (Gen. 1:31); even today “every creature of God is good” (1 Tim. 4:11), and “nothing is unclean in itself” (Rom. 14:14). To be sure, the Bible teaches that men are totally depraved in a moral sense, since sin has extended to the whole man, including his mind and will (Rom. 3; Eph. 2). But total depravity is to be taken in an extensive sense (affecting the whole man), not in an intensive sense (destroying the very essence of man).

When the theist says that evil is no “thing” (substance) he is not saying evil is “nothing” (that is, unreal). Evil is a real privation. Blindness is real—it is the real privation of sight. Likewise it is real to be maimed—it is a genuine lack of limb or sense organ.

Evil is not mere absence, however. Arms and eyes are absent in stones, but we would not say that stones are deprived of arms and eyes. A privation is more than an absence; it is an absence of some form or perfection that should be there (by its very nature).

The form or perfection that should be there (by its very nature) is what God started with. Evil came later. So God did not create the devil/demons or the fallen world – He created perfect angels and perfect humans who messed up. But the beauty is – He knew it would happen like that, and He allowed it because He loves us anyway.

Sources I will be using (so far):

Chapter 5: Is God the Source of My Suffering? / “Jesus Among Other Gods” by Ravi Zacharias (Thomas Nelson, 2000).

Chapter 21: The Problem of Evil / “Introduction to Philosophy / A Christian Perspective” by Geisler and Feinberg (Baker Books, 1980).

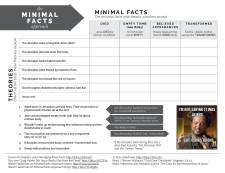

Five opposing positions you must choose from:

1. Evil exists, therefore the Creator does not exist. This explanation contradicts itself because it implies an objective, transcendent moral law (which is possible to implement within the physical universe, but is not ‘sustained’ by it), which only exists if God exists, and then denies the existence of God.

2. All is god (pantheism) and there is no evil (see Dawkins quote in #3). Hinduism explains perception of evil as induced by ignorance (Zacharias, 120). However, Hinduism’s doctrine of reincarnation, of paying your debt of karma (known to Jews and Christians as the debt of sin — but they see the consequence as death, complete separation from God, rather than seeing the consequence as…), having to suffer through another life (although an infant has done nothing to earn your debt… and what debt did the first human incur?) — inadvertently acknowledges the reality of evil while completely missing the point (see number 5).

3. There is no such thing as evil, because evil implies an objective, transcendent moral law (which is possible to implement within the physical universe, but is not ‘sustained’ by it), which only exists if God exists, and God does not exist. This explanation cannot logically demand an explanation for why God allows evil – it does not allow for the existence of God or evil.

“In a universe of blind physical forces and genetic replication, some people are going to get hurt, other people are going to get lucky, and you won’t find any rhyme or reason in it, nor any justice. The universe we observe has precisely the properties we should expect if there is, at the bottom, no design, no purpose, no evil and no other god. Nothing but blind, pitiless indifference. DNA neither knows nor cares. DNA just is. And we dance to its music,” [Richard Dawkins, Out of Eden (New York: Basic Books, 1992), 133.] You’ll never believe this, but I wrote “this is the music we dance to” and “let’s go wig out on the dance floor” in my faith thread before I read this quote from Dawkins. I was inspired by a sermon given by a visiting pastor from New Mexico, who used an illustration about a deaf man who tried to dance without hearing music. I was also inspired by a comment made by a person from another forum (the wig out thing). I wasn’t aware Dawkins had also said something similar. Stuff like this happens to me all the time.

4. Dualism: “good and evil in eternal opposition”.

5. God allows evil because He cannot compel us to love. “In a world where love is the supreme ethic, freedom must be built in,” (Zacharias, 118). Evil is the result of our not choosing to love God (and everything He is about).

*******

The first and fourth positions are the ones that bring up all the interesting “problem of evil” arguments.

***

A form of what some call evil has been brought up. The suffering of an innocent. The cause of all suffering is that this is a fallen world, this is not the world as God would have it, the world that would result if we all followed His will. That world would have no suffering (and some of what we would now call suffering would be endured with more strength/love). That world is in the future. This is the world that is necessary in order for that world to come about.

If it is always up to Him to end that suffering (of an innocent), then it is never up to us. Why should it never be up to us? Should God only and always end the suffering of the innocent — how do you think that would effect the psyches of the guilty? To whom did Christ come — those who are innocent, or those who are guilty? What would you do if that suffering was ended — give God the glory, or figure the suffering ended naturally? Have you asked God to end that suffering? What have you done about that suffering, but moan about a God you don’t believe exists — moan about how He can be so unjust and evil as to allow an innocent to suffer — when you deny that very evil? We are the stewards of this earth and every living being in it. We are given the responsibility of doing what we are moaning God should be doing. Such moaning is passing the buck. This is reality — and you are the tool God would use to end that suffering. Stop b****ing and start a revolution!

***

Zondervan’s NASB study bible note on Job 2:10 — “Trouble and suffering are not merely punishment for sin; for God’s people they may serve as a trial (as here) or as a discipline that culminates in spiritual gain (see 5:17; Deut 8:5; 2 Sam 7:14; Ps. 94:12; Prov 3:11-12; 1 Cor 11:32; Heb 12:5-11).”

***

Replace the first quote with the second quote (both taken from “Introduction to Philosophy / A Christian Perspective” (Geisler, Feinberg) —

(1) If God is all-good, He will destroy evil.

(2) If God is all-powerful, He can destroy evil.

(3) But evil is not destroyed.

(4) Therefore, there is no all-good, all-powerful God.

(1) If God is all-good, He will defeat evil.

(2) If He is all-powerful, He will defeat evil.

(3) Evil is not yet defeated.

(4) Therefore evil will one day be defeated.

And, I will discuss (if you want) the idea that “this is not the best of all possible worlds”. The argument:

(1)If there is a morally perfect God, then He must always do His best, morally speaking.

(2) But this world is not the morally best world possible.

(3) Therefore, there is no morally perfect God.

The counter-argument:

The problem with this argument from a theistic standpoint is premise 2. First, it may be that this world is not the best world but only the best way to get to the best world. This world may only be a precondition of perfection, the way tribulation is a precondition to patience, and the like. Second, the argument contains an ambiguity in the word possible. Does it mean “best world logically conceivable” or “best world actually achievable”? It may very well be that in the progress of the world toward its final point of perfection, this world is the best world presently achievable. Perhaps God is maximizing good in the world today and at every moment, given the limits of (a) human behavior and (b) the stage of progress toward the final goal. Today’s world is certainly not the best world conceivable and (humanly speaking) hopefully is not the best world ultimately achievable, but it could be the best world achievable today.